The Covid-19 pandemic, social isolation, quarantine and border closures came to a shock to many Australians. However, these drastic measures were not without precedent. In 1919 an eerily similar scenario played out as Queensland authorities battled to repel the Spanish Influenza, as this article written by Dr ANASTASIA DUKOVA of the Queensland Police Museum demonstrates.

In the last months of 1918, Australia was preparing for an outbreak of a novel influenza. The Commonwealth Government became aware of the new virus in July that year. Locally, it was known as ‘Pneumonic Influenza’ but internationally, it was called the ‘Spanish Influenza’. Spain was mistakenly identified as the origin of the outbreak when the Spanish king fell ill, and reports of his

sickness emerged. In reality, pockets of disease were registered at the London Hospital and Aldershot barracks from 1915 onward. The disease first reached epidemic proportions in garrisons throughout the US in 1918. It then travelled with the American troops to France and eventually across Europe.

In November 1918, the federal conference in Melbourne regulated Australia’s response to the looming health-threat. Ships that arrived with an infected person aboard were mass-inoculated and quarantined. The first case on shore was registered in January 1919, in Melbourne. Soon after, the virus spread to Sydney. Anticipating an outbreak, the Australian states gradually closed borders.

While trying to curtail the spread, the Commonwealth Government ordered compulsory inoculations of its staff. Some refused to comply.

In February 1919, Queensland applied to the Commonwealth Government for a restraining order to prevent returning troops from landing at a mainland quarantine station. Nevertheless, on 4 February, 260 soldiers landed and were quarantined at Lytton. Four soldiers broke quarantine that very night.

The disease was extraordinarily virulent, with a mortality rate of 2.5% among the infected. There were reports of people seeming healthy in the morning and dead by evening. It was more common for the illness to last 10 days followed by weeks of prolonged recovery. A range of sources all described the early signs of infection as ‘a chill or shivering, followed by headache and back pain.

Eventually, an acute muscle pain would overcome the sufferer, accompanied by some combination of vomiting, diarrhoea, watering eyes, a running or bleeding nose, a sore throat and a dry cough.’

Cyanosis, a bluish tinge to the skin, was a tell-tale sign of this infection. The flu, or grippe, infected roughly 2 million Australians in a population of about 5 million.

Despite a range of preventative actions, widespread infection and quarantine measures led to significant food and medical supplies shortages. Brisbane saw its water supply installation interrupted (every link in the work chain broke down because of the virus). Telephone exchange was disrupted, telegraph, postal services, banks and gas supply.

Annual reports presented by Police Commissioner Urquhart to the Parliament indicated Queensland police resources were stretched. Although the department nearly caught up with the personnel shortages following the war, there were still not enough officers ‘to meet requirements and carry a full 8-hour day’.

Borders closed

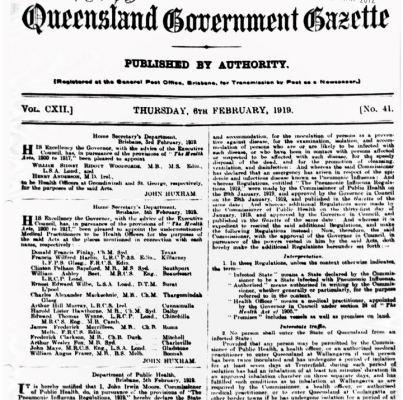

From late January to May 1919, the Queensland and New South Wales border was closed to help stop or at least slow, the spread of the Influenza virus into the state. The Health Acts 1900 to 1917, authorised the Queensland Commissioner of Public Health to issue regulations for state intervention of a person’s civil rights such as mandatory examination, detention and isolation of anyone likely to have been infected or who had been in contact with anyone sick. In1919, regulations issued by John Moore, the Commissioner of Public Health, empowered Police Officers to use reasonable force required to prevent any breach, or to apprehend any person, who had committed or was suspected of committing a breach of the public health laws.

On 28 January 1919, Queensland Police Commissioner Urquhart issued instructions to stop all persons from crossing into Queensland from New South Wales. Inspectors at Toowoomba and the Depot were directed to provide necessary help to all border stations by means of extra men and horses. Soon after, an additional officer was sent to the border towns of Coolangatta and Wallangarra. Eventually, 11 more officers from the Depot were sent to Coolangatta, equipped with 2 Bell tents, 22 brown blankets and 11 x bush rugs, waterproof sheet, pillows and slips and bed covers, for their accommodation and use.

Initially Coolangatta, Wallangarra and Goondiwindi were the only towns with dedicated border crossing points under Pneumonic Influenza Regulations. Though Wallangarra camp was located entirely within the territory of New South Wales, it was run by the Queensland government and health officials. The government’s decision to rigidly adhere to only three entry points resulted in a significant number of applications for exemptions from the public. In the face of such pressure, the government soon relented and established a medical screening process allowing bona fide Queenslanders to return to the state via Wompah, Hungerford, Wooroorooka, Adelaide Gate and Mungindi. Border patrols were also operating out of Killarney, Stanthorpe, Texas and Hebel among other locations.

During one of these patrols, Constable George Ruming (Reg No 1217) was seriously injured on duty. Constable Ruming was ‘patrolling the borders to enforce the quarantine regulations in the vicinity of Hungerford, when his horse fell and he was badly hurt, being knocked unconscious.’ He resigned from duty in October.

Between March and June 1919, 16 men were charged with breaching Pneumonic Influenza Regulations with fines ranging from £2 to £20.Most men charged were locals with the addition of two sailors from British Columbia, Canada.

An outbreak among the police stationed in Petrie Terrace and Roma Street barracks in Brisbane followed in mid-May 1919. In Petrie Terrace 25 out of 44 policemen had to be hospitalised and 20 out of 117 men got sick in Roma Street. The total strength of ordinary constables in Brisbane stood at 269. This means a third of that number, or approximately 90 constables, would have been

available for the round-the-clock 8-hour-shift to police a population of 190,000. A loss of nearly 50 men to infection would have been an extraordinary strain on the department.

First deaths

Constable Michael Joseph Flynn (Reg No 988; 2231), who was stationed at Petrie Terrace depot when he got sick, was the first police officer to die from Influenza. He died few days after hospitalisation at the Isolation Hospital set up in the Exhibition Grounds. Constable Flynn’s family was also hospitalised, a week earlier. Michael’s wife, Mary Beatrice, succumbed to the disease soon

after being admitted, on 12 May. One of their two children was reported to be in critical condition.

Mary Agnes was 4-years-old at the time and Michael was 6. They both survived the infection.

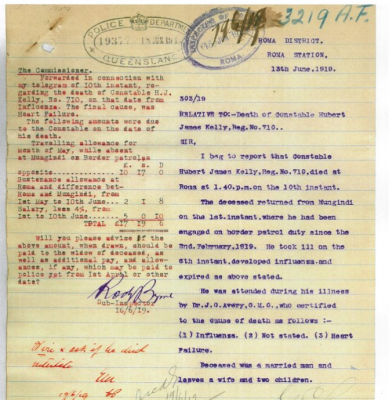

On 1 June, Constable Hubert James Kelly, who was assigned to Mungindi Border Patrol from 2 February 1919, returned to Roma. Constable Kelly was severely asthmatic and a regular tippler which seemed to help him cope with his asthma. Kelly returned unwell and given his respiratory issues his condition deteriorated quickly. He was placed on sick leave on 6 June, but his health worsened again and rapidly. Kelly died four days later at the hospital, on 10 June 1919.

The official cause of death was Influenza and heart failure. Kelly’s death devastated his family, wife Mary Bridget neé Maguire and two sons aged 5 and 6 years old, personally and financially. Kelly’s wife received a lump sum payment of £191/12/6 but as there was no widows’ pension fund to support families of the deceased officers, the family was soon in financial distress. In November

1921, Mary Kelly applied to be a female searcher at the Brisbane Watchhouse as she was advised there was a vacancy, however, she was misinformed.

On 11 June Acting Sergeant Hennessy and Constable Muir of Toowoomba Police Station were taken to the hospital suffering from influenza. They both recovered.

The total death toll for the force was two officers, Constables Flynn and Kelly.

The same week, on 14 June 1919, Dr Clark inoculated the Cairns police contingent, most likely with little effect, as agreed-upon standards for vaccines were still lacking. However, if nothing else, these vaccination attempts helped ‘to deconstruct existing biomedical knowledge’ which undoubtedly aided epidemiological advances that benefit us today.

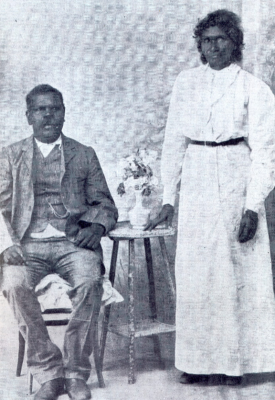

Tracker Corporal Sam Johnson was another Queensland Police Force casualty of the outbreak. Johnson was stationed in Longreach when he contracted the virus and died on 22 June 1919. Born about 1877 in Charleville in western Queensland, Sam was a member of the Bidjara people. He was a highly respected horseman and tracker with a quiet and sincere disposition, well built, and fit. He gained renown in 1902 following his role in the Kenniff brothers’ case and murders of Constables Doyle and Dahlke. The trial of the Kenniffs included significant and damning evidence by Sam Johnson. Being the sole survivor of the police party that arrived at Lethbridges Pocket, Sam was subjected to intense cross examination attempting to discredit his testimony. Johnson was survived by his wife, Limerick, who moved to the Rockhampton area later in 1919, where she died in 1921 and was interred at the Rockhampton Cemetery.

Border patrol

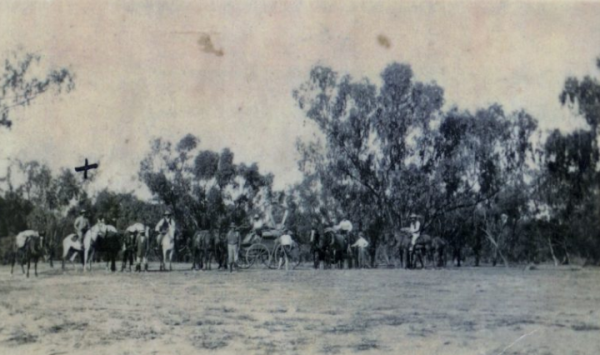

All officers on border patrol had to keep an individual diary, while Inspectors and Sub-Inspectors were required to report to the Commissioner on a weekly basis. These notes revealed that Constable Gray stationed at Adelaide Gate, Charleville Police District was provided with three camels by Lucas Hughes, the manager of the Nockatunga Station. The camels were said to be the only means available to Gray for border patrolling through the Western Desert Country. He had to employ an Aboriginal man from the station to help handle the animals. One camel later died, and the owner was compensated £20 for the death. Elsewhere in the Charleville district, border patrol officers had the use of three Howard brand bicycles.

In recognition of the arduous duties performed by the patrol policemen, every day for duration of the border closures, each officer’s pay was supplemented by 7/- per day. The men were at the higher risk of infection due to likely exposure to infected persons.

In late March 1919, Mungindi seems to have become a hot spot for Border Breakers, including women and children. In early May,

the virus finally crossed into Queensland and soon after the government re-opened the borders, as the authorities were no longer able to justify the lock down despite the appeals to keep the borders shut. As a result, all border patrol officers were recalled back to their usual stations.

Penalties for breaching Pneumonic Influenza Regulations ranged from fines of two to 20 pounds to short term imprisonment. In one case, from 12 February 1919, a man travelled to Blackall from the southern border over 600 kilometres, before he was located. He was subsequently isolated for 7 days and then prosecuted for breaching the regulations. The offender admitted to crossing the border at Mungindi, walking to Dirranbandi, then back to Thallon via Warwick, Toowoomba and Brisbane before being arrested at Blackall.

In 1997, the 1918 pneumonic influenza was identified as the H1N1 Influenza A of swine and human subgroup. It is now part of a routine vaccination program.

– Sections of this article were researched and written by Dr Anastasia Dukova, QPM, in collaboration with Dr Patrick Hodgson, James Cook University.